There are 18 players a side on field at any one time in an Aussie Rules football game. There are 12 eggs in a dozen carton. Count them. Under the 2012 TCP Code, service providers will need to know how many ‘Offers’ they have. At least, they’ll have to be able to identify each ‘Offer’, and that’s not always as easy as identifying a single footy player or an egg.

There are 18 players a side on field at any one time in an Aussie Rules football game. There are 12 eggs in a dozen carton. Count them. Under the 2012 TCP Code, service providers will need to know how many ‘Offers’ they have. At least, they’ll have to be able to identify each ‘Offer’, and that’s not always as easy as identifying a single footy player or an egg.

‘Offers’ are a fundamental building block of the Code. For instance, every Offer must have its own ‘Critical Information Statement’ or CIS. So it’s important to understand just what an ‘Offer’ is, and when you’re looking at ‘two Offers’ or just ‘one Offer with variations’.

Starting point: The Code’s definition

The Code defines ‘Offer’ this way:

Offer means a current, standard in‐market plan containing pricing that is made by a Supplier for the provision of Telecommunications Products, which is available to any individual Consumer or Consumers as a class and includes, without limitation such offers made in Advertising.

Read it a couple of times and you’ll see that it sort of explains the point, but it’s not crystal clear. Let’s think about it some more.

Telecommunications Products

For practical purposes, ‘Telecommunications Products’ means voice and/or data carriage services, including any associated equipment the service provider supplies.

An Offer is a plan

That’s a critical thing to notice: ‘Offer means a … plan’. Now, ‘plan’ is not defined by the Code. To really understand what an ‘Offer’ is you need to work out what a ‘plan’ is, or at least what the TCP Code considers a plan to be.

What’s a ‘plan’?

The Code seems to suggest that:

A plan is an offer to provide a voice and/or data carriage service:

- with certain technical features (eg ‘This is a phone service. You can make and receive local, national and international phone calls, and calls to mobiles.’)

- with certain pricing arrangements (eg ‘This costs $99 a month and for that you get free local and national calls and 75c calls to mobiles.’)

- with certain billing and payment arrangements (eg ‘This is a prepaid service’ or ‘ This is postpaid and requires direct debit.’)

- with certain bundling requirements (eg ‘We only offer this ADSL service in a bundle with a fixed line voice service’ or ‘This ADSL pricing is only available in a bundle with a fixed line voice service.’)

- with certain other legal terms attached (eg ‘This is subject to our SFOA, and a minimum term of 24 months.’)

- with certain eligibility requirements (eg ‘You can only take up this offer if you are serviced by an on-net exchange.’)

- with certain restrictions and exclusions (eg ‘The included value in this offer cannot be used for international calls.’)

- with or without associated equipment (eg ‘This offer includes a handset.’)

Besides that, the Code also seems to use ‘plan’ to mean the contract between service provider and customer that arises if the customer accepts the ‘offer’ of a ‘plan’.

So, without going into too much legal or linguistic theory, a ‘plan’ is both the product that a telco offers to the world, and it’s the contract that arises if that offer is accepted.

OK, so what does this mean about ‘Offers’?

When it comes to defining ‘Offers’ the Code is only using the word ‘plan’ in the first sense. It means ‘a plan we offer’ not ‘a plan you have already signed up to’.

So, in theory, if two arrangements are the same ‘Offer’ or ‘plan’ if they have:

- the same technical features

- the same pricing

- the same billing and payment arrangements

- the same bundling requirements

- the same legal terms

- the same eligibility requirements

- the same restrictions and exclusions

- the same associated equipment.

And if any of those things are not the same, they are two different ‘Offers’ or ‘plans’. So, for instance, they’d each need their own Critical Information Summary.

That’s the logical result, but in practice it’s not so black & white.

For instance, imagine two plans where the only difference is that:

- One costs $99 a month and the customer gets a paper bill.

- The other costs $97 a month and there’s no paper bill.

Is that ‘two Offers’ or ‘one Offer with two bill media options’? If we treat any variation as a separate Offer, there are going to be a huge number of CIS statements out there.

Common sense dictates that one CIS should be used for multiple products that are basically the same but with some variations. That’s what Internode did with its first CIS.

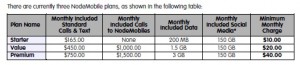

Arguably, the ‘Starter’, ‘Value’ and ‘Premium’ packages are three different plans or ‘Offers’. But it seems pretty reasonable to put them all into a single CIS. It’s pretty clear what it’s telling the reader, and probably a lot easier to understand than three separate CIS’s.

Arguably, the ‘Starter’, ‘Value’ and ‘Premium’ packages are three different plans or ‘Offers’. But it seems pretty reasonable to put them all into a single CIS. It’s pretty clear what it’s telling the reader, and probably a lot easier to understand than three separate CIS’s.

But how far can you go loading lots of options into one CIS?

We think there are three limits on how many different product permutations you can load into one CIS.

The two page size limit

First, a CIS can only be two pages long, and it can’t be in micro-print. So in some cases, service providers will find that although a set of product permutations could logically fit together in a single product summary, it’s just too hard to shoehorn them into the available space. Somehow, they’ll need to be broken up into separate CIS’s.

The need for clarity

We anticipate that Communications Compliance and ACMA will be reasonable about (what are arguably) multi-Offer CIS’s, up to the point that they become too complex to make sense of. If a telco produces a ‘one size fits many’ CIS that you need a tertiary degree to work out, we don’t think the regulators will be happy.

Very different offers

It’s hard to see how you could ever justify rolling a prepaid and a postpaid offer into one CIS. Maybe you could, but it seems unlikely. If two (or more) variants are seriously different in one (or more) significant way/s, that suggests they really do need separate CIS’s.

So, identifying ‘Offers’ is a an imprecise science

There’s real room to debate what differences or options turn something from a single plan with multi-options into multiple Offers. And there’s room to argue that the best way to treat some multiple Offers is by combining them in a single CIS.

We expect that as long as the CIS is fulfilling its informative function, the regulators will be flexible. But the constraints listed above always need to be kept in mind:

- Are we keeping to the two page limit?

- Is the CIS clear?

- Are any combined products/options within the CIS basically the same thing in various ‘flavours’?